The Finance Function in Action: The Nature of Operations

The term "operations" is quite broad as it describes a company's financial structure. In previous lessons we have investigated the many facets of operations. For example, in Part 1 of the Money Flow module we looked at the nature and scope of accounting activities in monitoring and maintaining operations. Parts 2 and 3 of the Money Flow module reviewed basic financial statements and used these statements to track money flows through the organization's various operating units. Part 4 of the Money Flow module described capital budgeting methods and the analysis of cash flows necessary for applying certain capital budgeting techniques. Part 5 described the nature and importance of the firm's dividend decision. Part 6 discussed the techniques used for financial planning; the Money Flow module described the nature of the purchasing function in operations.

In this section of Financial Resources we take a broader view of the corporation by explaining functional areas associated with operations. A functional area is simply a recognition that a particular corporate division does a certain thing or is engaged in specific activities. For example, the function of cash management would logically be related to managing the inflows and outflows that are generated as a result of carrying out operations. In large corporations this function would be handled by a cash management division.

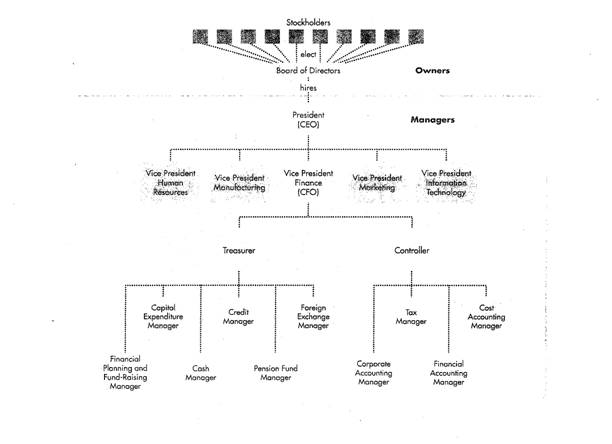

An organization flow chart: The best way to integrate the various functional areas of operations is to use a general organization flow chart.This graphic gives a broad-based overview of the decision channels that run from the stockholders, through the Board of Directors, and down though the company president and the various vice-presidents and divisions. The decision channels connect the operating divisions based on what these divisions do—their functional activities.

A representative organizational flow chart is presented in Figure 10-1 below. Keep in that mind that this is a typical functional flow chart; it is not meant to describe the organizational chain of command for any specific company. For example, the organizational flow chart of Toyota would look quite different from that describing (say) Smith Barney or Allstate Insurance. Keep in mind that to be complete the chart includes both finance and non-finance functional areas. Figure 10-1 is typical of a manufacturing facility.

Figure 10-1. A typical manufacturing organization flow chart

The graphic is reasonably self-explanatory. The specific finance areas are:

- The vice president of finance (CFO): The CFO answers to the president of the company (the Chief Executive Officer).

- The treasurer.The treasurer reports to the CFO: Answering to the treasurer are the capital expenditures manager, the credit manager, and the foreign exchange manager. Also answering to the treasurer are the following sub-divisions: financial planning manager, cash manager, and the pension/retirement fund manager.

- The controller: The controller (sometimes called "comptroller") also answers to the CFO. The controller "controls" by primarily monitoring current and projected accounting statements. Answering to the controller are the tax and cost accounting divisions. Sub-divisions answering to the controller are the corporate and financial accounting mangers. The cash manager might also report to the controller as well as to the treasurer.

Not shown in the graphic is the purchasing division. This division would probably be located directly under the vice president of manufacturing and would report to the CFO. The other non-finance divisions (e.g., human resources, manufacturing, marketing, and information resources) report directly to the company CEO and indirectly to the CFO. The position of the CFO division in the center of the second tier of divisions is purposeful. Financing the company in an appropriate manner can only occur if the CFO has knowledge of all divisions listed in the second tier. Obviously the CFO and CEO must have a close working relationship.

A democracy: As you can see from the graphic (and assuming the company's stock is publicly-held), control of the company is structured as a democracy with the stockholder/owners placed at the top of the organizational chain of command. All divisions and sub-divisions of the corporate organization must act in the best interests of the stockholders. If this does not occur, the stockholders can vote out the Board of Directors, as well as, the CEO and those below the CEO. The separation of ownership and control of the company is the crux of the agency relationship in a corporate democracy setting. We will discuss this relationship in the ethics section of this Lesson Plan.

The owners of the company (the stockholders and large institutional investors) can vote on the members of the Board of Directors and can exert pressure on the Directors to choose a CEO to their liking. The Board of Directors in conjunction with the CEO have the responsibility for developing a strategic mission plan and for guiding the company towards meeting its longer-run mission goals. Major capital expenditures decisions and the hiring/firing decisions of key managers in the organizational chain also come under the control of the Board.

The CEO is responsible for putting into action the day-to-day operations of the company's short-term tactical operating assignment and for carrying out the directives of the Board. As the President of the U.S. reports periodically to the Congress, the CEO must periodically report to the members of the Board.

Often the vice president of finance (CFO) is also the chief operating officer (COO) and reports directly to the CEO. The main decision areas under the CFO's responsibility will be the treasurer and the controller. Typically the treasurer has direct responsibility for managing the firm's cash and marketable securities, for planning its capital structure, and for selling the firm's stocks and bonds to raise capital. The treasurer will also oversee the corporate pension plan and will be responsible for assessing and managing risk.

If the firm deals in an international market for sales or the purchase of inputs a major risk would be exchange rate risk. This special type of risk would be the responsibility of the foreign exchange manager who would be responsible for arranging appropriate hedging strategies. The treasurer supervises the credit manager's activities, the inventory manager, and the director of capital budgeting. The controller is also typically responsible for the various accounting and tax activities of the company. If the firm is publicly owned, both the CEO and CFO must certify that the firm's financial statements are accurate (this requirement is part of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and will be described in more detain below).

Figure 10-1 as it pertains to the overall operating structure of the company is perhaps mis-leading in one important way—it does not emphasize the many information flows that occur in carrying out operating directives. The graphic tends to suggest that information directives flow from the CFO downward through the various operating divisions.

In the modern corporation this is not necessarily the case. Many firms are organized so that information feedback can occur. For example, the cash manager (with the permission of the treasurer) might report important cash-using events directly to both the treasurer and the CFO simultaneously. In early corporate organizational structures in the U.S. such an action would have been considered "jumping rank." With modern information technology (to be described later in this Lesson Plan) it is easy and relatively inexpensive to make the appropriate parties aware of important events impacting operations. The important requirement is that all relevant parties be contacted simultaneously and that directives from higher to lower levels of management be issued from one division. The philosophy is that the company should carry out operations in a unified manner. As was described previously on purchasing, information flows may include vendors and suppliers outside the company. Modern information technology has made this philosophy actionable by maintaining a two-way routing of information.

Summary: As you can see from the Figure 10-1 the nature and success of operations will be determined by how well the various functional areas of the business are integrated so that the company acts as one unit.